Comicking Part 2: Writing and Thumbnails

- At March 01, 2011

- By Laur

- In blog, processes

5

5

This is Part 2 of a series of posts I’m writing about how I made Final Track, a 34-page shojo manga I worked on as my submission for the Yen Press New Talent Search.

Now that you’ve got some ideas, it’s time to choose one and focus on crafting it. I’m going to be honest with you and admit this is the most difficult part of the process for me. You’ve really got to be patient during this process because if you care about creating an interesting, meaningful story, it comes with a price: dedication, perseverance and time.

Ever since I was introduced to the craft of screenwriting (writing for TV and movies) by my writing partner (@nathango), I started paying more attention to elements of stories I previously used to gloss over. I started running into terms like character motivations, conflicts and resolutions and felt like I was learning vital notions I could use in creating comics. I’m sure there are plenty of great books for how to write comics, too, but I’ve been in love with movies longer than I’ve been reading comics so it was just a matter of preference.

It certainly helps to have someone with you through the brainstorming period in which your story takes shape. I’ve worked with Nathan, my co-writer on Final Track, on projects before and I know we care enough about creating a good story that we can get into lengthy debates over important things. We talk about characters first and what their journey will be like. Then, one of us makes a rough outline of how we think things will go. Once we get to this stage, I take over and make my first pass at dialogue.

Scripting

When I script, I just use MS Word and change the layout orientation to landscape and create two columns per page. Recently, I’ve also tried just having the page view showing 2 pages simultaneously. The Insert>PageBreak function is especially useful when I want to write for a new page. I do this to get a feel for where the page I’m writing falls: right or left. (In this case, my assumption is based on a printed comic book layout.) That way I can plan important scenes like surprises on a left page so you don’t see it coming until you turn the page. I also have an easier time figuring out where I can insert a double page spread to make sure it actually takes up facing pages.

If I have a page count limit, I find it helpful to break the story into chunks and determine how many pages each chunk should take up. If you know about act breaks, you can break your story into however many acts you want (for example, the typical number of acts are 3 for a movie — this is easy to understand: beginning, middle and end). This way, you know what scenes should be extended or cut depending on page availability.

I have a lot of fun with dialogue and enjoy writing for comedy. It’s when I script and play with the characters’ voices in my head that I see the comic come to life. But sometimes, I can get carried away with ideas. So getting feedback as early as this part in the process helps me avoid making painful changes down the road when things are harder to edit. Having a working script doesn’t make things final anyway. Often, I create thumbnails alongside the script especially if I want to see how scenes break down on a page. This helps me include visual notes that I don’t have to write out on the script.

Thumbnailing

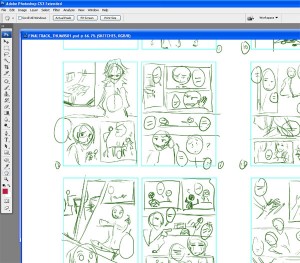

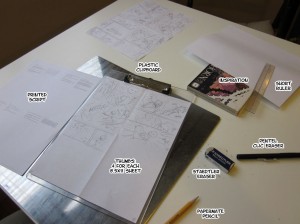

With thumbs, I’ve been wavering back and forth with drawing them on paper and using a tablet on Photoshop. Thumbs don’t really need to be polished which is why I can do them on scrap pieces of paper. But when I’m moving scenes around different pages, having the option of cutting and pasting panels and sequences onto new pages frees me up creatively so I don’t have to erase and redraw anything. I can concentrate on the flow of the story.

Flow is really what I pay attention to when I’m working on thumbs. Does it make sense? Are the elements on the page properly guiding the reader? What are the most important aspects I want to highlight in the scene? All of these are questions I ask when drawing the stick figures in the boxes because I want to control the experience of the viewer and make them see what I want them to show them. If you don’t understand what’s going on in a panel of a comic page, it’s likely the result of poor composition choices.

Questions? Suggestions? I’d love to hear from you!

Previous Post: Comicking Part 1: Ideas

Next Post: Comicking Part 3: Character Designs